Subversion or Submission: Gender, Romance, and Patriarchy in Fantasy Gamebooks

The discussion of gender as it relates to interactive media might seem a tiresome or almost self-evident one, considering that such entertainment is most often associated with a male audience; but, as these forms of media have evolved, it is necessary to consider the ways in which attempts at gender inclusion have been made, whether successfully or not. Through an in-depth analysis of fantasy gamebooks – which I’ll loosely define as a genre that includes elements of magic, adventure, and fantastical creatures, often weaving romance into the narrative, whether subtly or overtly – it is evident that, while a variety of strategies have been employed, each method either deliberately subverts or achingly adheres to traditional gender codes. Indeed, through a cross-examination of three drastically different game book series – HeartQuest, Endless Quest, and Find Your Fate Junior - Golden Girl, gender stereotypes are applied in varying degrees, with regard to both choice and character depiction, demonstrating a mixed range of patriarchal and misogynistic factors, as well as an occasional desire to highlight and then reject such traditions.

First, though fantasy may appear to be among the most gender inclusive of main gamebook genres, creating explicitly feminine protagonists (as in HeartQuest), powerful female warriors (as in Golden Girl), or gender neutral characters (as in Endless Quest), the wider representations of gender depend heavily on secondary genres like romance and adventure. Fantasy, when paired with romance, tends to create more stereotypically unflattering and socially limited depictions of females, while the fantasy/adventure genre provides either gender neutral characters or female warriors. It seems that, based on the continuation of a series like Endless Quest and the relatively short lifespans of both HeartQuest and Golden Girl, the extremes of either the traditional female romantic or the combative warrior woman are the least popular, while a gender neutral protagonist is appealing to both male and female readers. This strategy is, perhaps, the most immersive and widely appealing experience because it allows readers to project their own personalities onto characters who possess both traditionally feminine and masculine characteristics, which is, after all, the most accurate representation of real people who don’t neatly fit into either restrictive box.

Romance, Misogyny, and Agency: Character Depictions & Choice in HeartQuest

Through HeartQuest, a fantasy/romance series set within the world of Dungeons & Dragons, publishers made a clear attempt to create a female fanbase by the inclusion of romantic choices in addition to typical gamebook decisions pertaining to the direction of the overall quest. While there is a lack of strict structural consistency, with books one and two taking the form of tall arboreal graphs, books four and six following a linear-heavy graphing structure, and books three and five producing graphs of a smaller arboreal structure, the series is consistent in its array of choices while still presenting an intriguing variety of female protagonists. Though all of HeartQuest’s heroines are preoccupied with the prospect of romance, they vary in levels of agency and ability; for example Ring of the Ruby Dragon allows the reader to inhabit the character Chandelle, who only provides support and companionship to the male adventurers and love interests whom she meets along her journey. While most of the remainder of the series presents females with magical abilities (which are largely used to play defensive roles rather than actively fighting alongside male companions), Isle of Illusion departs from this pattern by allowing the reader to play the character of Licia, a warrior daughter of a Viking. Though Licia’s father indicates his wish that she stay at home, which is actually a choice early on in the book, the character is able to resume the quest abandoned by her long lost brother. Despite the fact that Isle of Illusion offers the only martial character of the HeartQuest series, Licia is still dominated by a slew of male characters, from her controlling father to her model brother, and finally to her love interest, who actually smacks her on the bottom with his sword, resulting in humiliation and perpetuating the exhausted yet relevant symbol of the male wielding the phallus.

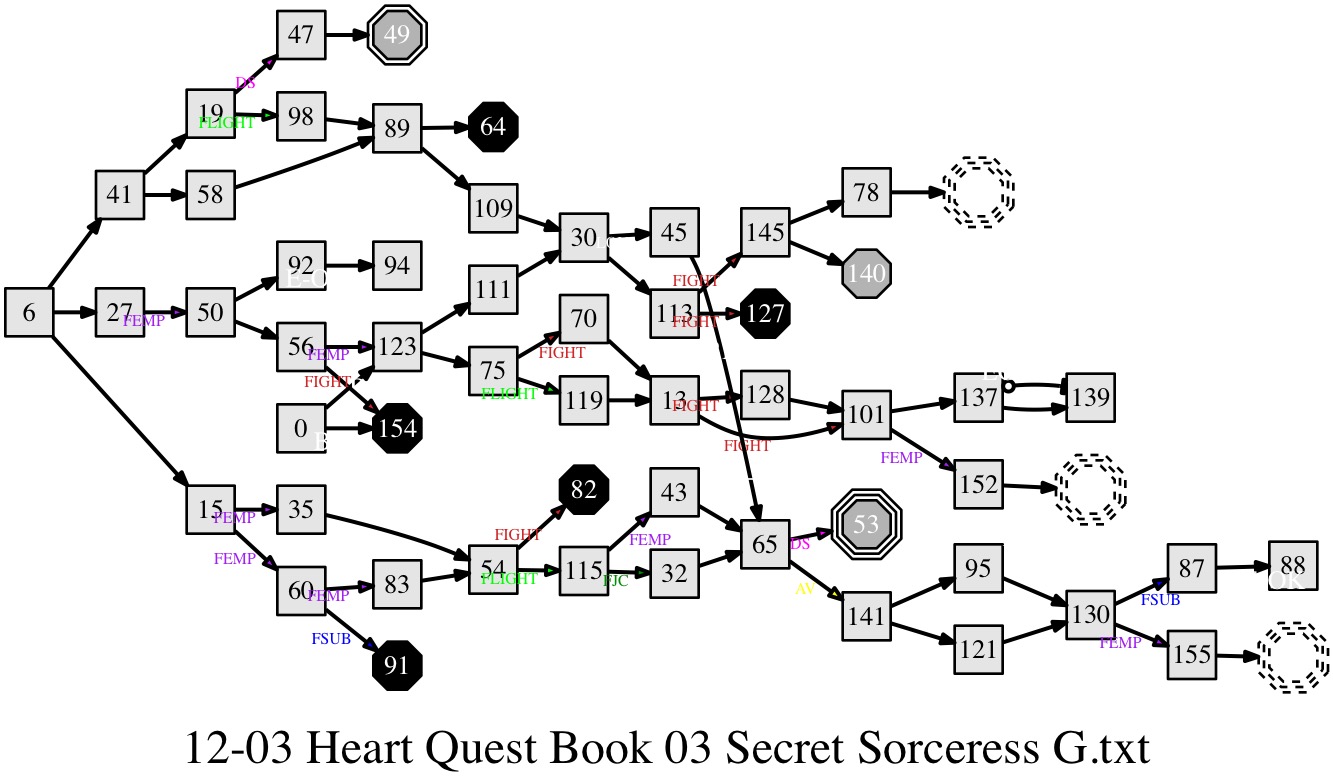

Similarly, the third book of the series, Secret Sorceress (a graph of which can be found on page four), offers a depiction of the all-powerful father figure that embodies the patriarchal fears of women across the ages. Through the character of Mialie, a mage and secret heiress of a kingdom, the player escapes Ungaar Castle, where Mialie’s adoptive father, Ungaar, has raised her as a slave. Despite the odds, Mialie finds love with Prince Shaw (69), and even faces the choice of making house with Shaw (where she contentedly passes the time gardening and decorating) at the aptly named Blissford Castle (53, marked DS for domesticity) or continuing on with her quest (141, marked AV for adventure). While choosing to live with Shaw in peace at Blissford Castle means that Mialie never discovers her royal pedigree, the ending is a happy one, as are all romance endings within the HeartQuest series. Contrastingly, choosing to follow through with the quest is rewarded when, with the help of Shaw, Mialie learns of her heritage but is immediately confronted with the choice of returning home to become the bride of the evil father-figure Ungaar, who professes his love for Mialie through a letter, creating a love triangle that is characteristic of the series. Disturbingly, Mialie seriously contemplates the choice of returning to Ungaar, hoping to mend his evil ways with her love (130 → 87, marked FSUB for female submission), a decision that produces an ending designated as “okay” because it sidesteps death and is made of free will. While choosing to stay with Shaw and ignore Ungaar’s message produces the ultimate happy ending (marked as a triple octagon), with both romance and ascension to the throne, the very option of returning to Ungaar is problematic because it illustrates the belief of submissively bowing down to the patriarchal figure, who systematically manipulates and abuses Mialie.

While choices relating to patriarchy and misogyny within the HeartQuest series peak in Secret Sorceress, the father figure is central to all of its gamebooks, especially with regard to gaining a father’s consent in matters of life and romance that affect later gamebook choice, highlighting the series’ problematic roots in traditionalism that likely led to its relatively short lifespan. Moreover, romantic choices reflecting both female jealousy and an enjoyment in creating male rivalry, as well as the use of language like “wench-driven scow” when referring to a boat pulled by mermaids in Ring of the Ruby Dragon, depict stereotypically negative female attributes that make the HeartQuest series feel completely isolated from the real spirit of fantasy.

Gender Neutrality & Female Character Stereotypes in Endless Quest

In contrast, the Endless Quest series, one of the most successful American gamebook collections, favors a gender neutral approach to many of its protagonists, but still allows character depiction within the series to reinforce certain female stereotypes that overlap with HeartQuest, including domesticity (DS), female jealousy (FJC), and female seduction (FSED). To provide a brief overview, Revolt of the Dwarves casts the reader as Galen, who is depicted only in the artwork as being male, but, when choosing to follow the beautiful pixie, Whimsy, is exposed to a variety of negative assumptions about women. After choosing to follow Whimsy rather than banding with the dwarves, Galen expresses his attraction to the pixie, who immodestly accepts his compliments and agrees to journey alongside him purely because it is entertaining for her; she has no desire to help, but rather, regards Galen as an object, which is made evident during instances of jealousy and possessiveness between both a witch and a tree spirit. Interestingly, Galen, who appears quite childlike, is faced with the choice of continuing on his journey with Whimsy or being seduced by the overly sexualized tree spirit (116 → 53), who is depicted as being full-bosomed with dark eyes and a sly grin. This choice not only leads to a bleak ending, but also suggests that female seduction is dangerous and powerful enough to bewitch a prepubescent child. Moreover, while overpowering female sexuality perpetuates the stereotype of women as calculating seductresses, Revolt of the Dwarves also illustrates the tradition of females as keepers of the hearth and home, with Whimsy rewarding Galen with cooking, cleaning, and preparing a bed for him if he chooses to stay with her, further perpetuating traditional female roles within the fantasy genre.

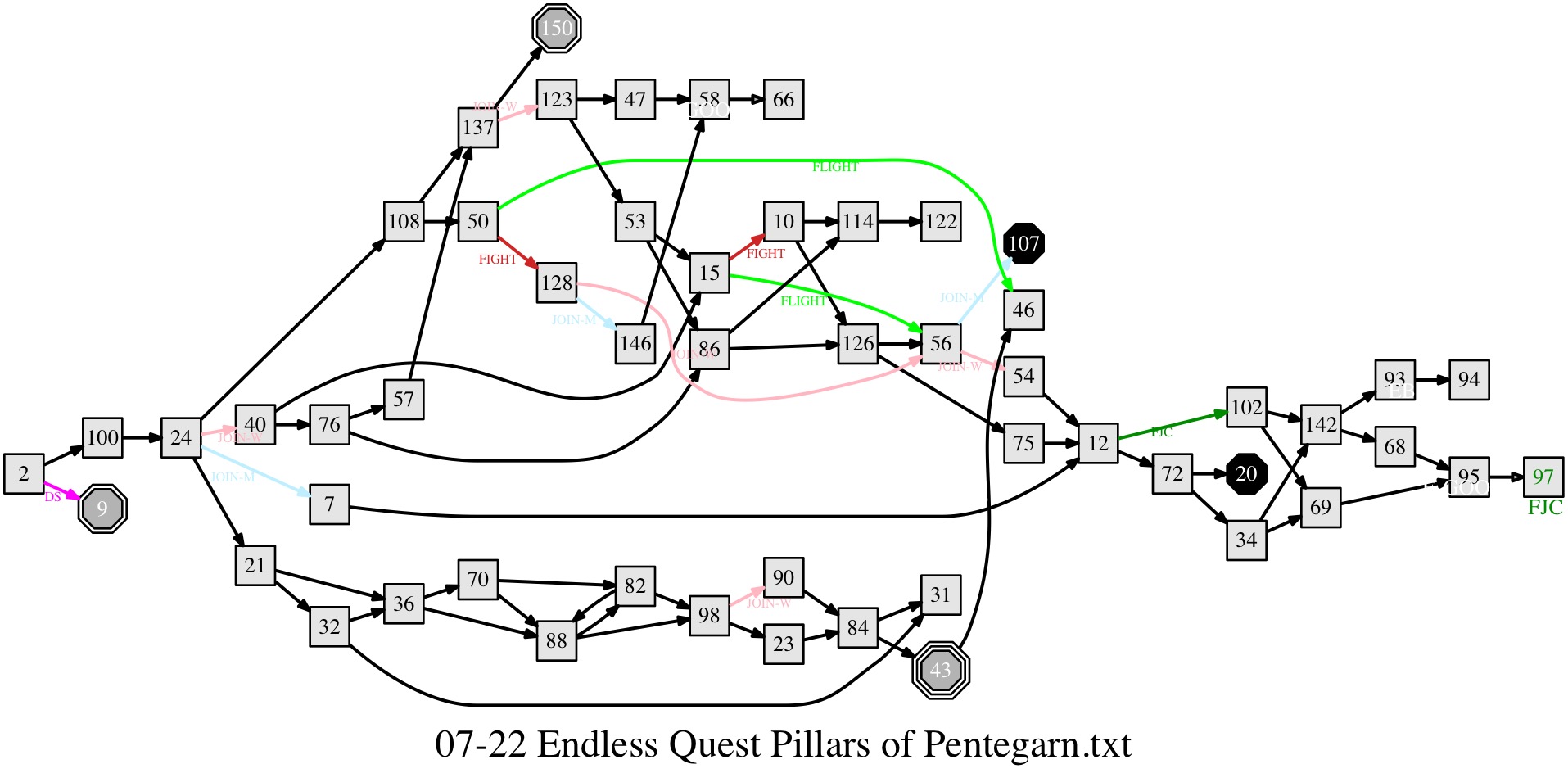

Perhaps most interestingly within the Endless Quest series is the gamebook Pillars of Pentergarn, which casts the reader as the gender neutral Jaimie, while also introducing the first female character of the series. Lydia is a beautiful elven thief who, though matched in appearance, strength, and even clothing by her male counterpart, Baltek, is mischievous and self-serving, while Baltek is portrayed as sacrificing himself for the team throughout nearly every storyline. Indeed, if a reader consistently follows Lydia’s advice and subsequent choices (shown in the graph below), Baltek will die scouting ahead (14 → 102) while Lydia unknowingly accuses him of taking the treasure for himself, demonstrating the expectation of women as covetous and suspicious. Moreover, Lydia’s passion for jewels ultimately leads her to try on a cursed ring, despite the warnings of the wizard Pentergarn, which nearly kills her and forces the reader to choose between saving Lydia or moving ahead for the good of the team.

Despite her many shortcomings, following Lydia’s advice will finally lead the reader to secure the treasure and claim Jaimie’s rightful place as heir to a kingdom, but this ending is only reached through Lydia’s greed. In fact, once the treasure has been recovered (at the hefty cost of losing both Baltek and Pentegarn), Lydia leaves young Jaimie without a backward glance as the protagonist puzzles over the prospect of ruling a kingdom. In short, the beautiful, cunning Lydia is portrayed as a one-dimensional female character who, despite her overall help, which is purely coincidental, is self-centered, possessive, and suspicious, offering zero redeeming qualities even as a successful ending is reached. Moreover, when contrasted with the heroic Baltek, who is identical in costume and demeanor in the book’s illustrations, one wonders why the male counterpart appears to partake in the journey for the sole purpose of aiding in a good cause, while the female character is materialistic and impulsive enough to tamper with a cursed ring. In this light, female heroes within the fantasy genre are silly and even dangerous when compared to their selfless, noble male alternates.

Feminocentrism & Female Warriors in Golden Girl

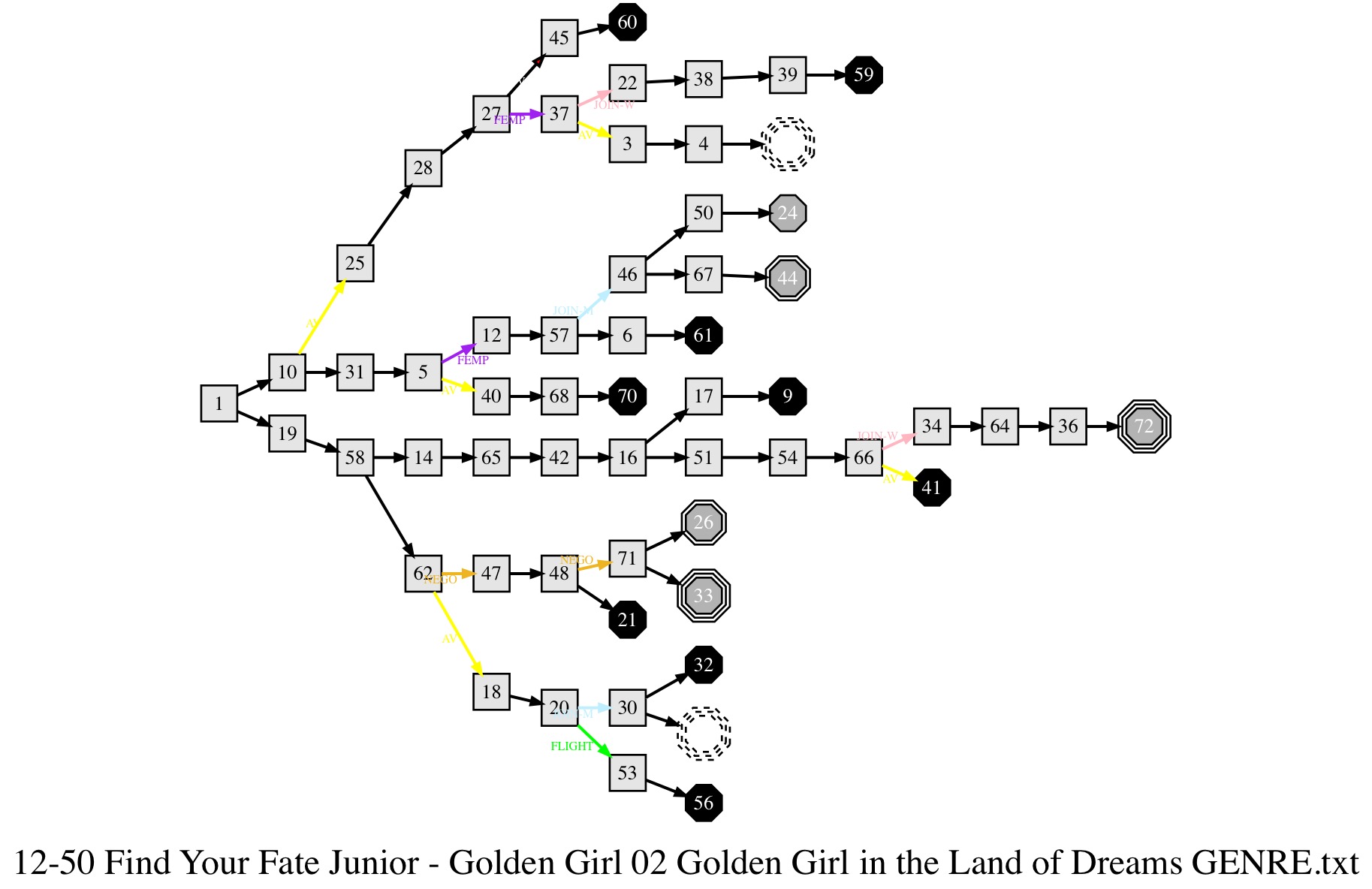

Throughout the short-lived series of Golden Girl, writers and publishers attempt to appeal to a female audience by presenting a strong female protagonist who is surrounded by an equally powerful group of warrior companions. Though one male, the dopey but loyal Prince Kroma, regularly journeys with Golden Girl and her band of female warriors, the element of romance is not explicitly introduced until the second gamebook of the series, Golden Girl in the Land of Dreams. Intriguingly, choices that empower the female characters are often rewarded, with Golden Girl succeeding in negotiating with her enemies (marked as NEGO), a strategy that fails in both Endless Quest and HeartQuest, yet seems to appear more often as a choice in gamebooks presented from a female perspective. Moreover, while the option of flight (marked FLIGHT in green) garners mixed results in general, it is rewarded in Golden Girl because it is paired with the careful consideration and discussion of her female companions. In fact, when Golden Girl strays from this logic-based approach to questing, most notably when she briefly lusts after Garnet, who is actually the Dragon Queen in disguise, she dies (27 → 45). If, instead, Golden Girl chooses to heed the warnings of her female companions (27 → 37, marked FEMP for female empowerment), she not only destroys the Dragon Queen but finds love with Prince Kroma.

Though depictions of female teamwork, successful negotiations, and impulsive lust being punished might appear to challenge many traditional depictions of women, it is important to note that romance was still believed to be a necessary element of the Golden Girl series when attempting to draw a female audience. While the same cannot be said of male fantasy game books, it is also problematic that Golden Girl’s happiest endings (marked by a triple octagon) all land her with the stereotypical “nice guy,” Prince Kroma, who is depicted as idiotic and inappropriately lighthearted, even laughing as he is rescued by Golden Girl from a deadly cocoon in Golden Girl and the Vanishing Unicorn. This characterization, while placing a male as the damsel in distress, also suggests that women should, perhaps, look to the male friends they have rejected in the past, and thus gives in to “nice guy syndrome.” Furthermore, Golden Girl is described as “enjoying Kroma’s jealousy” when she briefly falls victim to the charms of the handsome Garnet, further perpetuating both the idea of the female love triangle, as well as the notion that women crave jealousy in their male companions. So, while the Golden Girl series can be viewed as taking strides in female empowerment with regard to choice and gender depiction within fantasy gamebooks, it still reinforces certain distinctly female negative stereotypes which, when paired with its short lifespan, suggest that this strategy was largely ineffective amongst women.

To conclude, through three dramatically different fantasy gamebook series, it is evident that depictions of women have often reverted to traditional, dated stereotypes in the hope of appealing to a wider female audience. However, considering the success of the Endless Quest series, one can deduce that a gender neutral, generic approach to character is the most applicable to a wider audience, regardless of gender. For example, contemporary interactive media in the form of role playing games like Skyrim, Fallout, and Knights of the Old Republic provide the option of choosing gender before embarking on any journey, with romance serving as an optional component of the game with little to no effect on the overall outcome. Moreover, role playing games have adapted to accommodate queer relationships, suggesting that depictions of gender and sexuality have evolved to the point of being all-encompassing in many cases. Still, it is both important and necessary to consider the ways in which such progression in interactive media has been made possible, which is, in part, thanks to studies of predecessors like Choose Your Own Adventure gamebooks.