Discovering the Treasure of Libri-Giochi: Pedagogical Value in the Italian Gamebook Collection

Overview

My research topic looks at Italian educational gamebooks in the Demian Katz collection. I began by looking within the category foreign language gamebooks at Italian works in general. The Italian collection was small in quantity, 83 total books, but diverse in genre and complexity. I began by selecting works that were translated from English editions, but realized that original Italian gamebooks were more diverse and interesting to research. Typically, Italian translated versions of English gamebooks had little variation in either content or lexia choice structure so the traversal graphs of the original and the translation were identical. Instead of focusing on translated adaptations, I chose instead to research a trend I noticed among gamebooks, that is, the self-reflexive and pedagogical uses of Italian gamebooks. As a student raised in the American education system, I was never formally introduced to gamebooks nor were they part of my curriculum. Therefore, I found that the value placed on Italian gamebooks a compelling topic that could provide insight into Italian culture.

To create the traversal graphs for comparison and display I used the application yEd. The organic layout and hierarchical layout are used to sort the game-stories within larger works. Most translations were done using the Google Translate Optical Character Recognition software or facilitated by graduate students familiar with Italian.

Gamebooks Analyzed (for Educational Uses):

- Costruire i Libri-Gioco by Andrea Angiolino

- *Stop Al Vandalismo Grafico*: Elementary School Competition published by the Department of Educational and Youth Policies of the Municipality of Rome [a boxed set of twelve gamebooks]

Of the Italian gamebooks that I worked on, the typical works generally belonged to the adventure and fantasy genre that had been originally published in English gamebook series (e.g. Choose Your Own Adventure, Time Machine, Goosebumps). These adaptations tended to be long, complex, and produce identical traversal graphs. The English versions served as a template for the translated versions. Within original Italian gamebooks I found a small group with an emphasis of the pedagogical uses of gamebooks, rather than using (or viewing) the gamebook for solely entertainment purposes.

The Italian gamebooks I chose to analyze are gamebooks that provide theory and practice of using gamebooks for education, being created for children and by children. Generally, these works had short lexias to teach morality and literacy, and consisted of only a few choices that produced simple story graphs. This simple construction of the gamebooks allows for easier writing and reading.

Examples

In La Corona Del Re Sole, the introduction mentions the importance of gamebooks to teach those with “limited literacy” to read better, both for their moral betterment (“rende moralmente migliori”) and to prepare them for the rough journey of life (“preparazione a quel percorso spesso accidentato che è la vita”). The book uses “psycholinguistic devices” such as shorter lexias to motivate the reader, as well as strategic vocabulary placement (i.e., unfamiliar words placed among familiar words).

Costruire I Libri-Gioco (Building Game Books) is a manual for how to construct and use gamebooks. The manual is not itself a gamebook, but examples of mini-gamebooks are intertwined throughout its pages. One example features a story teaching morality by saving Rome from vandalism: La Città in Pericolo (The City in Danger). This story is part of a collection of twelve gamebooks created by elementary school students: Stop Al Vandalismo Grafico. The collection contains one work by each participating group of students’ gamebooks, along with their illustrations. Stop Al Vandalismo was organized by The Education Department of the City of Rome in order to raise awareness and teach students about the consequences of vandalism, especially on monuments. Gamebook construction was used to directly influence students’ morality.

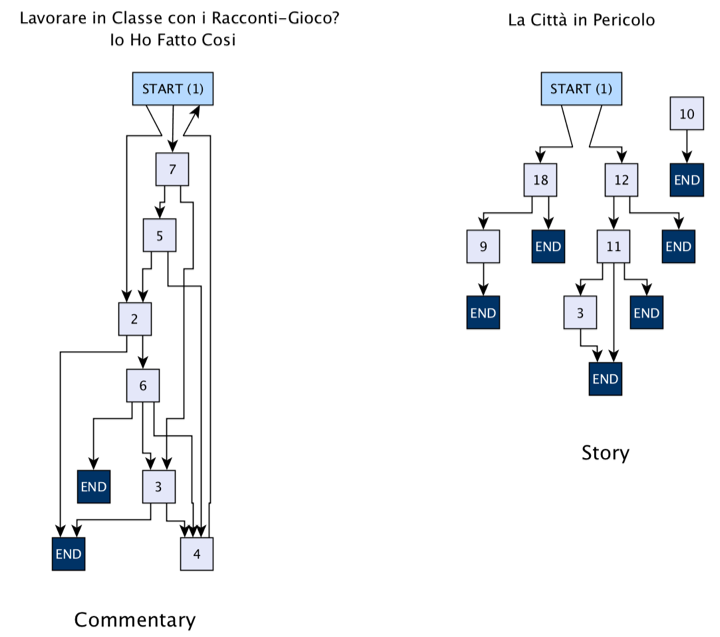

Interestingly, Costruire i libri-gioco provides meta-commentary on Stop Al Vandalismo Grafico. Christian Zambon, the Italian teacher who led the students that created the story La Città in Pericolo, provides commentary on the construction of gamebooks as a classroom activity and about La Città in Pericolo specifically. Zambon’s commentary is also written in the form of a gamebook called Lavorare in Classe con i Racconti-Gioco? Io Ho Fatto Cosi. The commentary is displayed on the page margins of Costruire I Libri-Gioco, adjacent to the lexias of La Città in Pericolo that it comments on. Graphs of both the students’ story and the teacher’s commentary are featured below.

Zambon notes that even though La Città in Pericolo skips paragraphs and that “using all the numbers is just a question of elegance, not a real need,” the story still came in second place. The story’s bad endings deal with the protagonist having to pay a million dollar fine and being caught by the police after spray painting monuments in Rome.

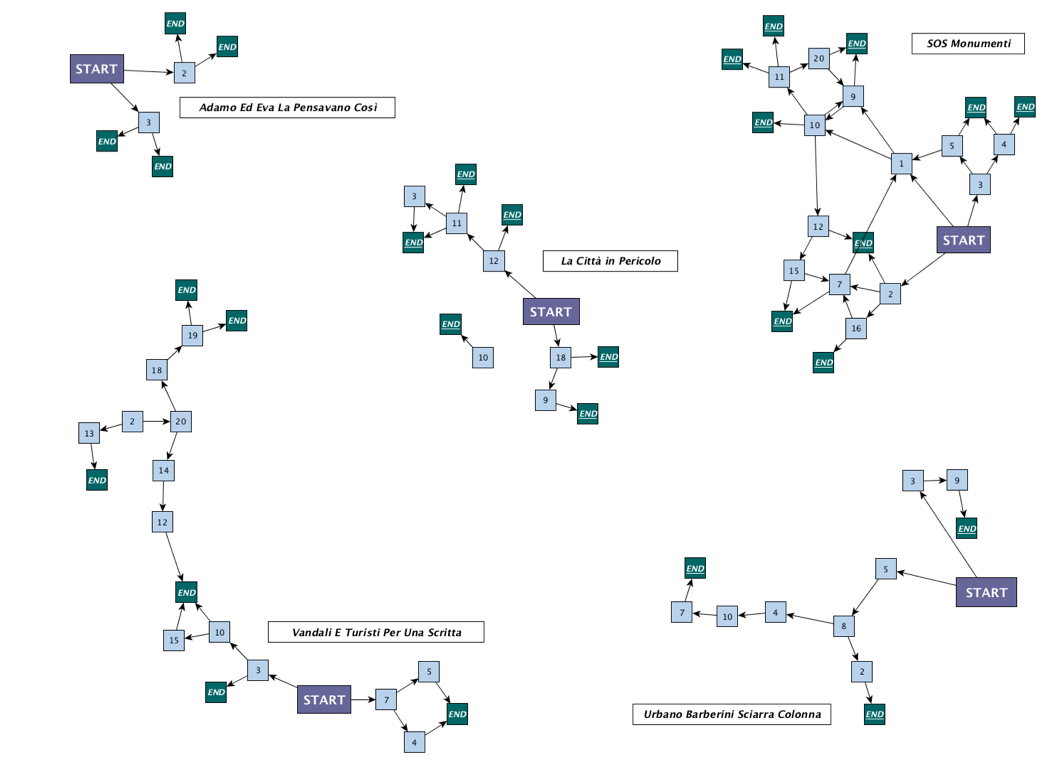

The Stop Al Vandalismo Grafico collection shows the diversity and creativity of each classroom’s stories. Some graphs are more linear, but each one begins with two choices or paths. Themes include religious imagery to interactive stories in the form of a board game. Featured in the graph below are five story graphs from stories in the collection written by elementary students: SOS Monumenti, Vandali e Turisti per Una Scritta, Adamo ed Eva La Pensavano Così, Urbano Barberini Sciarra Colonna, and La Città in Pericolo. This competition suggests that coming up with multiple endings is a way of teaching critical thinking by fabricating consequences for realistic situations. Additionally, Angiolino states that Italian teachers are “always hunting” for strategies like gamebooks that are novelties that help facilitate learning and claiming that gamebooks have linguistic benefits even for readers who do not have knowledge of the Italian language (i.e., these readers learn Italian more quickly and more effectively, through fun).

Findings

The findings of my research suggest that in America, there might be more of an entertainment culture attributed to gamebooks rather than using introspective practices that are associated with Italian gamebooks. Compared to the English gamebook collection, it seems that in Italy, gamebooks are more formally recognized in educational contexts by educational systems and local government. This suggestion is quite broad and would be supported by further research into the educational uses of gamebooks in both America and Italy. However, this research could work as a way to explore the pedagogical differences in the values of the American education system compared to the Italian education system. As seen in this analysis, vandalism and keeping the city clean is an important value in the Italian gamebooks represented here. Comparing values across cultures by studying foreign languages gamebooks would make for an interesting project in further research.